Aganta Burina Burinata or Orange, Grapefruit, Tangerine

Cumhur Gökova: "Living is a journey."

Some individuals prioritize life above all else. They stick to familiar paths, confront danger without hesitation, eschew competition, and neither demand nor provide explanations. Perhaps it's this very attitude that attracts life's most captivating journeys and presents them with its most exquisite adventures.

Cumhur Gökova stands as a prime example of such individuals, notably within the Turkish maritime industry. Throughout his life, Gökova embraced his own path unfettered. He traversed, explored, cherished, gained wisdom, and imparted knowledge. Ultimately, life metamorphosed into an odyssey for him.

We met Gökova on a day when he momentarily stepped away from overseeing the Gökova Sailing Academy, a venture he co-manages with his sons, to visit Istanbul. Entranced, we absorbed his heartening and inspirational tale.

Kayhan Yavuz: Let's go back to the beginning. When and where did your story begin?

Cumhur Gökova: My roots trace back to Adapazarı, specifically the Akyazı village. My father, a dedicated educator and a graduate of the Village Institute, instilled in me a love for knowledge. Wherever he went, he'd establish libraries. It was from these shelves that I first delved into travel and adventure literature, captivated by the likes of Jules Verne's 'Around the World in 80 Days.' These narratives ignited my passion for exploration.

In the late 60s, amidst escalating right-wing-leftist tensions, I found myself interrogated outside the school gates. 'Are you right-wing?' they'd ask. 'No,' I'd respond. 'Ah, so you're left-wing. Go through the other door.' But at the alternate entrance, the questioning resumed. 'Are you leftist?' they'd inquire. 'No, I'm neither rightist nor leftist!' I was uninvolved in political affiliations then, as I am today. Regardless, I approached my father with a bold declaration: 'Dad, I'm embarking on a journey around the world!' Concerned about the political strife, my father, ever supportive, responded, 'Go, son. I'll sell my jacket if needed to fund your journey.' So long as I steered clear of such entanglements.

KY: Wow! Well done! No one would have sent a young man abroad alone in that age, in that era. Your father was a brave man.

CG: Yes, it was! I was going to get a passport, I went to the governor's office. There were typists there, they did the work. The man looked at me, "OK, but," he said, "you are only 18 years old. You haven't done your military service yet. If you go abroad, they won't extend your passport, you'll stay there, you can't go back." I started crying because I couldn't go. The man said, "Stop, don't cry. We will make you two years older, you will do your military service. Then you can go." I started crying again. "I have a sister two years older, that won't work." You cannot imagine what the man said: "Fine, we'll make you twins!"

KY: No way!

CG: Yea! My sister and I appeared before the judge. My father was with us and my uncle was our witness. The judge looked at my sister and looked at me. "Son," he said, "tell the truth. Why are you trying to raise your age?" The typist had warned me beforehand. I immediately stood at attention, loudly: "To fulfill my patriotic duty as soon as possible, sir!" The judge looked at me and said, "People run away from military service, and you want to do military service? I'm doing it then, it's done." I grew two years older in one day.

KY: And straight to the military!

CG: Yes, the date was August 15, 1968. I became an aviator in the army, by chance. There they told me that the Americans have a training program called "Best of the Best". Five of you will be selected for this program and trained as instructors. Those who are successful in sports should come forward. I had medals in gymnastics from high school, I even ranked second in Turkey. They took me and a few other people and took us to Eğirdir, to the commando school. They were going to make us all commando instructors. Air parachute commando.

KY: You were going to go to Europe, but you ended up in Isparta.

CG: I was in Isparta and we were traveling in the mountains. How five men take over a town? How to land on a lake from the air in an operation? We practiced these things. Then we started training on "How to blow up a bridge." They give you the coordinates with a compass, you dive in, there are small boxes under the water, you place bombs in them. Of course, these are sound bombs, training material. Then you come out and wait. If those boxes explode at the same time, you are considered successful. But thanks to one of my friends at work, the bomb exploded at the wrong time because he set it wrong. I couldn't sleep for a week because of tinnitus.

KY: And that didn't deter you from having adventures?

CG: No. As soon as I was demobilized, I went to Europe. My family and relatives brought me to Edirne. I hitchhiked from Edirne to Switzerland, sleeping in the forest. Of course, I am a man who had commando training. I reached Switzerland in July 1970.

KY: Why Switzerland?

CG: One of my uncles lived there, in Zurich.

KY: Was that where your journey around the world began?

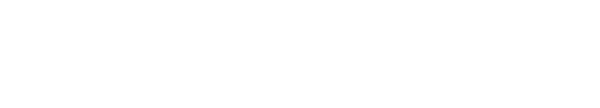

CG: Yes, but something occurred prior to that. We had a grandfather, Ahmed Zülfikâr Pasha, who was in exile in Egypt. My mother would frequently travel by ferry to visit him, despite the prevailing fear surrounding ferry travel at the time. Upon his passing, he bequeathed his entire estate to my mother, Mrs. Hikmet, with one stipulation: she must not share the inheritance with anyone. This left my mother pondering her next steps. If she accepted the inheritance, she'd possess more wealth than my father, potentially leading to unrest at home. On the other hand, if she divided the inheritance among her siblings, she'd be disregarding the pasha's wishes. Eventually, she reached a decision. She said to me, "Son, take that money and utilize it for benevolent deeds. But refrain from acquiring any property."

KY: Did your father intervene?

CG: No, when it comes to my Circassian mother, who can intervene! So, at the age of 20, I set off from Switzerland to Egypt.

KY: You weren't able to commence a world tour, but you continued traveling to various parts of the world, including Switzerland and Egypt...

CG: Indeed, the journey seemed to unfold on its own accord. By the end of 1971, I found myself in Egypt. There, I discovered an astonishing collection of musical instruments left behind by the pasha. Among them was a jukebox from that era... insert money, and it plays music from various countries. Selling off everything I could, I ended up at the airport with a suitcase brimming with Egyptian pounds. It was then that I learned taking Egyptian currency out of the country was prohibited. So, there I stood, with a suitcase full of money, unsure of my next move!

KY: How much money are we talking about?

CG: About 650 thousand dollars at the time.

KY: That's so much money! If you look at it in terms of purchasing power, 650 thousand dollars that day is 10 times more than today.

CG: Yes, but I could not use the money, or rather I could not get it out of the country. Anyway, I first settled in a hotel and then I started to go to the Pyramids every morning with a bag of Egyptian pounds. I approach the tourists, the bank gives me one, I give them 1.5, I give them 2. I slowly convert the money into German Marks, Swiss Francs. I convert all the money into foreign currency and go back to Switzerland.

KY: With 650 thousand dollars in your pocket.

CG: Yes, 650 thousand dollars.

KY: Is that when you began to take an interest in sailing?

CG: Here's how it happened. In Zurich, people would take boats out on the lakes. One day, I noticed someone standing near a boat and asked, "Is this your boat?" The young man replied, "No, I work on the boat. We rent it out for this many francs per hour." When I inquired about his pay per hour, and he responded, "I don't pay anything; I take care of the boat, and they pay me," something clicked. That day, I decided, "Alright, I've found my calling. I'm going to become a sailing instructor." It was a way to travel and earn simultaneously.

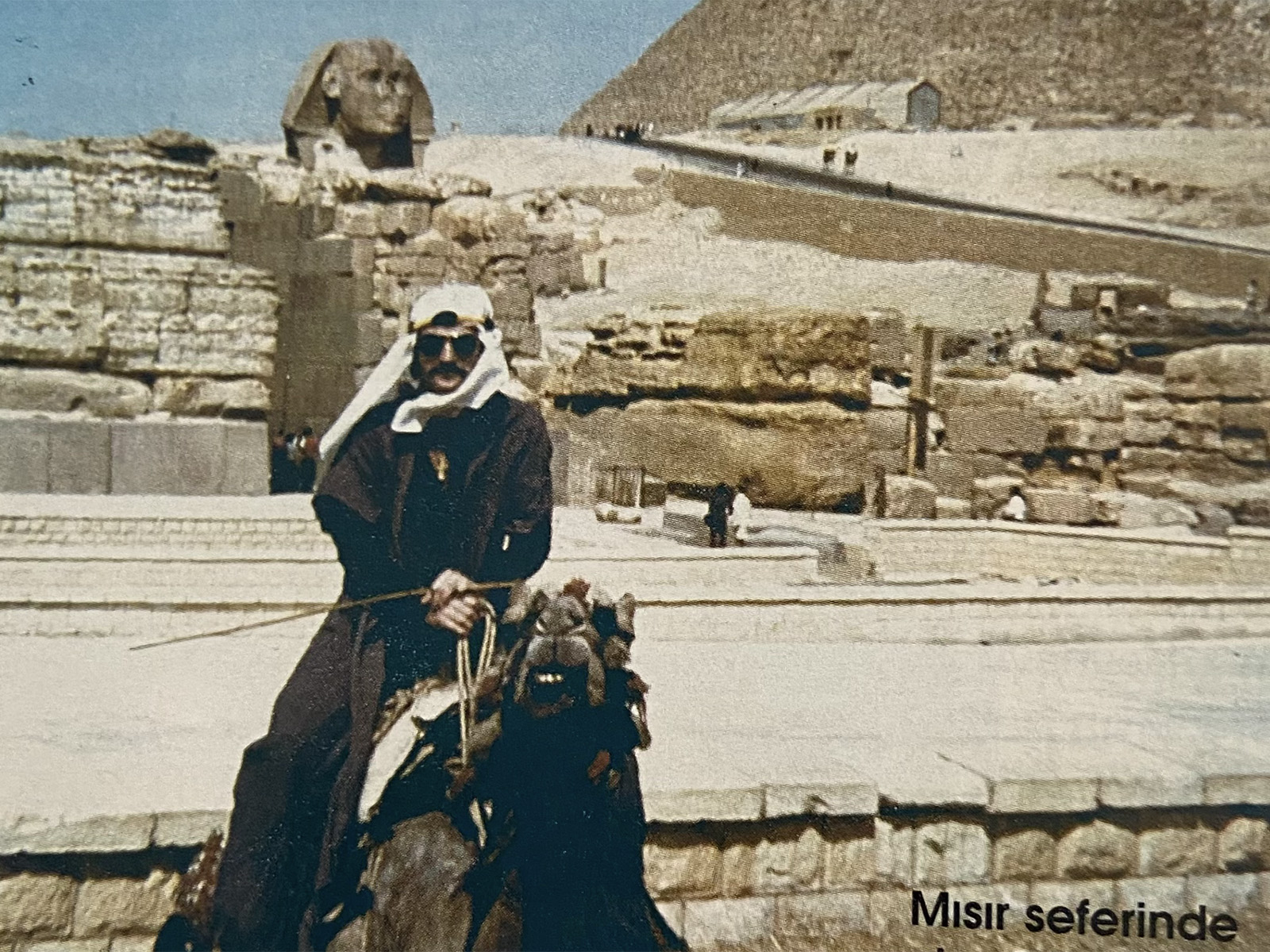

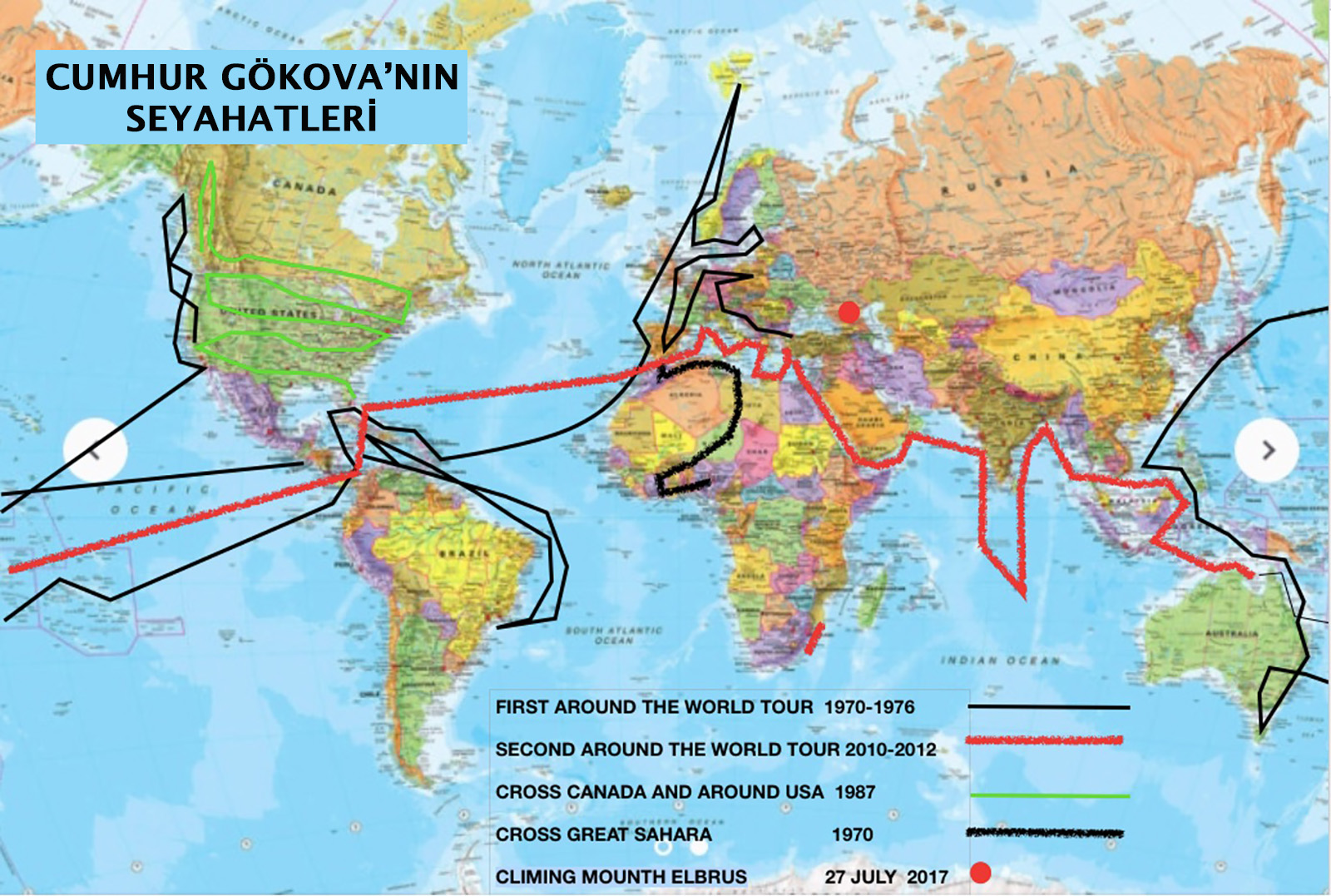

Of course, I always had my sights set on a world tour involving sailing. But initially, I wanted to explore Europe. With my close friend Daniel, I proposed, "Let's buy a jeep and tour Europe!" So, we purchased a "181 Volkswagen" and embarked on our journey. We covered everywhere except Czechoslovakia in that jeep. Later, I suggested, "Let's head to Africa!" This time, Daniel declined. Undeterred, I set off with my girlfriend at the time, Margaret Belche, along with the rifle her father had gifted me. We journeyed all the way to Nigeria, to Lagos. There, I sold the jeep, and we flew back to Switzerland.

KY: The year is 1973. So, you became the first Turk to cross the Sahara.

CG: Yes, I think I am.

KY: Then you ventured to the North Pole. This time, you became the first Turk to reach the North Pole.

CG: And it unfolded like this: Upon returning from Africa, I enrolled in a navigation course. During one class, the instructor highlighted the North Pole as the most challenging location due to magnetic declination, where metrics shift as you near the pole. This piqued my interest, and I resolved, "If Everest is our first conquest, the other mountains will pale in comparison." I turned to Daniel and declared, "We're heading to the North Pole."

Naturally, we needed a boat. Together, we journeyed to England and discovered a handmade vessel in Southampton. Initially crafted for a round-the-world voyage, the owner, unable to sway his wife, had held onto it. We purchased the boat. On April 1, 1974, our journey to the North commenced. We sailed through Oslo, Gdansk, Riga, St. Petersburg, and the Norwegian fjords—places untouched by Turkish presence. Finally, we reached Spitsbergen, where the sun doesn't set for 24 hours during certain times of the year. It was July 1974. Our ultimate aim was witnessing the "night sun," where the sun shines at midnight, casting the sky in a mesmerizing green hue.

KY: How long did it take you to do this tour?

CG: It took us three months. We went back to England before the end of the summer.

KY: Wasn't it hard? You went to the pole on your first boat trip.

CG: We were oblivious to whether it was hard or easy! Or perhaps, we were simply unfamiliar with the easy ones, allowing us to discern the truly challenging endeavors.

(At that moment, the phone rings. Mr. Cumhur invites his tennis instructor friend, who had seen his photo on Instagram and inquired about his remarkable fitness, to join him for a morning workout. Cumhur Gökova, despite his age, appears surprisingly energetic and sprightly. He attributes his vitality to a rigorous exercise regimen comprising 900 movements that he faithfully repeats every morning.)

KY: Sadun Boro sailed around the world between 1962-65. You hit the road a few years after him.

CG: We have always followed the path he paved. That's how I convinced Daniel. I said, "Look, he did it with his wife. We are two men, we can do it even easier." I call what I did between 1970-78 a "world tour", not a full world tour. Then I did the full world tour between 2010-12.

KY: Still, after Boro, you are the second Turk to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

CG: Yes. Atlantic crossings and world tours are considered separately.

KY: Your trip to the North Pole is actually the start of this "world trip". From there you sail straight to Gibraltar and down along the coast to Africa.

CG: I did not follow the usual route across the Atlantic. First, I went down from Tangier to Senegal and crossed the ocean from there. In November 1974 we sailed straight to the Caribbean. In 26 days, we crossed the Atlantic and arrived in Barbados! Then they said there was a carnival in Rio, so we went down to South America, and Rio became my favorite place.

KY: It seems you're not concerned about "let me finish this tour and make history."

CG: No, I never cared about that. I don't have a time limit, it's a way of life. My way of life has become "going".

KY: And then?

CG: My mother had a request from me. "Just send me a diploma," she said. I also wanted to get a job before the money ran out. I went to Canada. In Circassian society, we all choose one person as our life teacher. My life mentor was my aunt's doctor husband in Vancouver, Canada. In our village they called him Crazy Murat. He was a Galatasaray graduate, an extraordinary man.

First, I thought I'd be an underwater photographer, so I took a course. Then I thought I'd be a ski instructor, so I got a diploma. Then I became a tennis instructor. Since I'm an aviator, I enrolled in a pilot school, where I got a diploma as a fire extinguisher pilot. We fly the Cesna. I thought I would stay in that job, but I got bored flying alone. It felt like a prison next to the sailboat. I finally decided on sailing, because on a sailboat you can go wherever you want, drink your wine, invite your friends. It's not even a job! What's better than that!

KY: I guess that's how the process that made you have known as the "teacher of teachers" in the sailing world started.

CG: Yes, until I came to Turkey, the following method was followed for sailing instructors. After a certain number of candidates, the Federation would bring an instructor from England. The instructor would give the training here and make an exam. When I received a teaching certificate from England, this was no longer necessary. I became the first instructor and the number of my teaching certificate is "1". It is the "YY7 Instructor Trainer" certificate given by the Turkish Sailing Federation to only one person in Turkey so far. So, they started to call me "the teacher of teachers".

KY: Did you have many students?

CG: 14,141 students.

KY: Considering that the number of licensed sailors is currently around 5 thousand, this is indeed an incredible number. You have contributed a lot to the Turkish maritime industry both as a teacher and as an entrepreneur.

CG: I did a lot, but I didn't do it according to a plan. I tried to contribute to the issues that came to my mind, that I thought were missing. I brought the first foreign school branches to Turkey. Then I opened branches abroad. Schools in China, in Moscow, under the name Gökova. Free courses for children and young people to instill the love of sailing. Apart from that, I founded the Marmaris Sailing Club with four friends in 1989.

KY: Among the students you have trained, there are those who have traveled the world, well-known people, successful athletes. There are children and young people whose lives you have touched. One of them is Paralympic sailor Hüseyin Akbulut. How did you meet him?

CG: We met at the Marmaris market. Hüseyin was selling watermelons despite his disability. He was doing his job so well that I said, "Let me make you a sailor!" Suddenly, at that moment, I had this idea and he was so successful! First of all, he is Turkey's first disabled yacht racer and sailing instructor. He ranked first many times in Turkish championships and was selected for the national team. He won medals and cups around the world. Now he is a coach and has his own school in Marmaris.

KY: It's a beautiful story. But the sea also has a dark side. Storms, danger, piracy, accidents, unpleasant sides... What scares you the most at sea?

CG: Nothing scares me. Oh, I was scared only once, I remember now. The pilots wanted to form a group and cross the Atlantic. They had also taken a journalist with them, and he was going to do the interviews. Coming from the Caribbean, in a very rough weather, the cameraman lost his balance and fell into the water. I was only scared there. Because the waves were so big, so big that I couldn't see the guy. I would see him and then I would lose him. I told the three of them, "You're not going to do anything, you're just going to point at him with your finger!" When we reached him, that's when I felt relieved. We took the man on the boat, I saw that he wasn't scared at all, sir, he was sure that I would save him. Other than that, I don't remember being scared. I also got caught in an 80-knot storm. You know when you get on top of a wave and realize that the world is round, a storm like that. It was awesome. But I also use the storm to my advantage. The speed you catch coming down from the top of that wave is a very different pleasure.

KY: You are one of those who see every problem as an opportunity...

CG: That is the secret of happiness. The secret of happiness is to turn negative events into positive ones.

KY: Well, you have been at sea for years, you are one of the people who observe environmental problems most closely. On the one hand there is terrible pollution, on the other hand there are campaigns and efforts to raise awareness. How do you perceive the current state of affairs?

CG: Unfortunately, the situation is far from ideal. The effects of climate change are starkly evident, particularly in places like South Africa, where cows are going blind due to global warming. Halting this trend seems daunting. However, I've also noticed a positive shift in consciousness among our people in recent years. This awareness is increasingly apparent among trainees and even among friends who sail in the South. They're no longer indiscriminately discarding waste into the sea as they once did. This collective attention is a promising sign.

Environmental issues are both global and deeply personal. Many believe that forests are the primary purifiers of the world's air. However, the true heroes are the algae at the ocean's depths, diligently cleaning our planet's atmosphere. Thus, safeguarding our seas is of paramount importance. Now, at 74 years old, I've been fortunate to experience minimal health issues thus far. My vision has remained intact, which I attribute in part to my life at sea, the constant exposure to oceanic oxygen, and of course, regular exercise. Therefore, I urge everyone to embrace life at sea and prioritize the cleanliness of our oceans.

KY: The conversation came exactly where I hoped it would. You are very interested in longevity. As a sailor of many years, a "teacher of teachers" and a person who epitomizes health and happiness, I would like to ask you: How should young people take care of themselves?

CG: It's obvious what to do: Yoga every morning, Tibetan yoga. Otherwise, stay in the sun for 30 minutes a day and get plenty of oxygen. Walk in the fresh air every morning, at least six kilometers. No running, performance sports age you, stay away. You can walk barefoot on pebbles. I have never taken any medication and neither should you. And drink water. I always carry water, I drink water. And regular sex. Do these things and you'll probably live to be 100.

Interview: Kayhan Yavuz, Setur Marinas Highlights Editor