Prof. Dr. Ahmet Cevdet Yalçıner: The world’s best tsunami maps prepared for Istanbul

In recent years, we have witnessed several back-to-back earthquake disasters that have resulted in painful memories and expensive lessons. Despite thousands of warnings and extensive discussions, our earthquake experts have struggled to explain all the complexities. While there has been some awareness about earthquakes in our society, the same cannot be said about tsunamis. Nevertheless, our country is situated in crucial earthquake zones and has historically faced the danger of tsunamis.

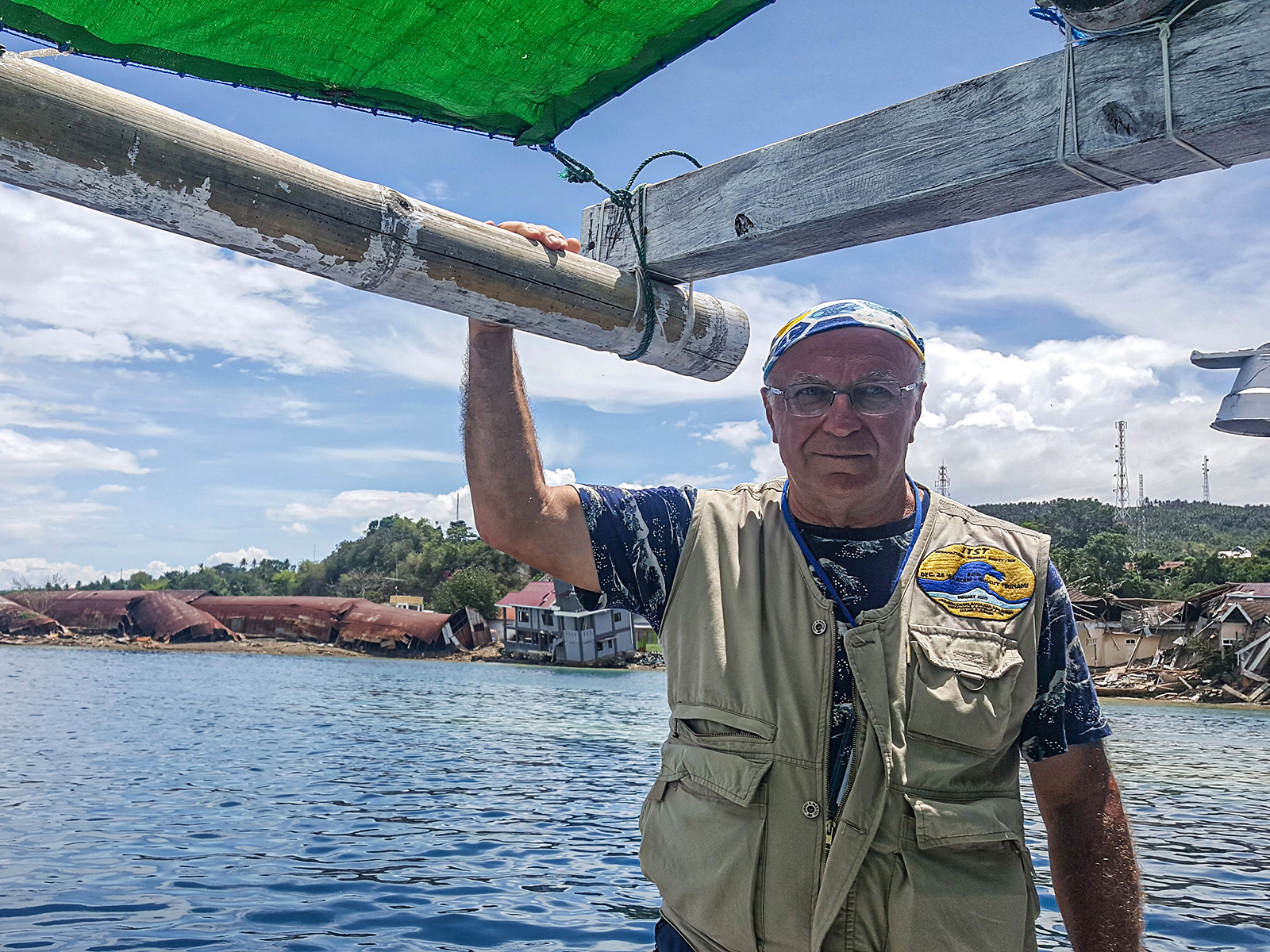

Fortunately, as a country, we have significant knowledge and world-class experts in the field of tsunamis. One of them is Prof. Dr. Ahmet Cevdet Yalçıner, who until recently served as the Head of the UNESCO North East Atlantic and Mediterranean Tsunami Warning System and is currently a faculty member at the Middle East Technical University, Faculty of Engineering and a member of the UNESCO Turkish National Commission Specialized Committee for Natural Sciences. We met with Prof. Dr. Ahmet and asked him the questions that are on the minds of our citizens who live in coastal areas, who are interested in the sea or who own boats. We received answers that enlightened us all, and at most points, were even groundbreaking.

Kayhan Yavuz: There seems to be widespread confusion about tsunamis. On one hand, some people believe that tsunamis are a Japanese problem and do not concern us because we do not have any oceans. According to this view, tsunamis can only happen in oceans and never in inland seas. On the other hand, there are those who believe that tsunamis can happen anywhere, even in places like the Golden Horn, Kuruçeşme, and Sarıyer. To begin our conversation on tsunamis, let's start with the basics: what exactly is a tsunami, and how does it occur?

Ahmet Cevdet Yalçıner: The phenomenon that we refer to as a tsunami is a type of ocean wave. It occurs when a large amount of energy is transferred to the ocean in a short period of time. This energy transfer can happen due to various reasons, such as a fault being broken by an earthquake or a landslide triggered by an earthquake. Settlements on the seabed that are triggered by an earthquake can also cause energy transfers. When these transfers lead to vertical displacements on the seabed, they create waves that we call tsunamis.

KY: Is it only earthquakes that transfer energy to the sea?

ACY: There are many reasons for energy transfer to the sea and many different natural phenomena that occur as a result. For example, energy can be transferred by wind or by atmospheric phenomena due to changes in air pressure. Astronomical causes include energy transfer due to the gravitational pull of the Earth, the moon and the sun. As we all know, this type of wave is called a tidal wave. They are long-term waves caused by the displacement of the low pressure center and the strong winds that occur around it, which usually occur in tropical regions with the effect of temperature and humidity. They are called "cyclone" or "hurricane" in English and "tropical storms" in Turkish and "typhoon" in Japanese. To summarize, there can be different reasons for the formation of sea waves. What distinguishes a tsunami from others is that it is a "seismic" activity that usually occurs at sea.

KY: So tsunami has nothing to do with the size of the wave. I mean, for example, surf waves are also very big, but people are enjoying themselves on them, let alone being scared.

ACY: Indeed, in English, "swell" is a term used to describe long, rolling ocean waves. In Turkish, they are referred to as "soluğan". In the ocean or seas, which can extend up to 4,000 kilometers from east to west, such as the Mediterranean Sea, storms caused by winds blowing from the land can create waves of varying amplitudes and periods. As these wave trains travel across hundreds of kilometers in open sea environments, the small waves within them lose energy and disappear, while the long-period, high-amplitude waves continue their journey and reach opposite coasts. In the Mediterranean and Black Sea, the periods of these waves can range from 6 to 15 seconds, while in the oceans, they can arrive at the coast as very large waves with a period of 20 to 25 seconds. Swell waves are generally very similar to each other, with a sinusoidal profile. Surfers can anticipate the arrival of the same wave at regular intervals, and as these waves approach the shore, they typically break smoothly, offering a perfect opportunity for wave surfing enthusiasts to practice their sport.

KY: Then here is where we are wrong. In order for a tsunami to happen, we expect to see 30-meter waves and witness brutal destruction like in Sumatra, Sri Lanka and Japan.

ACY: It is true that many of us tend to associate tsunamis only with the massive 30-meter waves seen in Sumatra or Japan. However, the primary factor behind the formation of such enormous waves is the magnitude of the earthquake, the length of the fault fracture, and the height of the fault throw. In the case of the Indian Ocean tsunami triggered on December 26, 2004, the fault throw was 25 meters, and the resulting wave can rise even higher when it reaches the shores. The larger the fault rupture, the bigger the resulting tsunami wave. Whether the wave height is 30 meters or 50 centimeters, the impact and drag forces are significant as the wave advances in the form of a flowing mass of water. In fact, a 50-centimeter tsunami or flood current that is knee-high can be strong enough to drag a person.

In the recent years, instrumental measurements have detected several tsunami events in the Aegean Sea. Notable examples include the Gökçeada tsunami in 2014, the Bodrum-Kos earthquake-induced tsunami on July 21, 2017, and the Sığacık tsunami on October 30, 2020, which dragged almost 300 boats from the marina. After the major earthquake on February 6, 2023, a tsunami in Iskenderun Bay and Eastern Mediterranean with a 25 cm amplitude was detected by mareograph stations in Arsuz, Erdemli, Kyrenia, and Gazimagussa. These tsunamis differ in size, but they are all classified as tsunamis. Interestingly, the Japanese word for tsunami, which means "harbor wave", is not based on the size of the wave but on its effectiveness in harbors.

KY: We have a lot of information about the earthquake history of our country and region. In other words, we have earthquake data going back centuries. Based on these, modeling and even predictions can be made. Do we have such a historical background on tsunamis?

ACY: In fact, The Mediterranean holds the oldest known records of tsunamis due to the presence of early civilizations and accumulated knowledge. Dating back approximately 7 thousand years, one of the earliest recorded tsunamis was caused by an undersea landslide off the coast of Norway in Storegga. Another significant event occurred around 1630 BC when the eruption of the Santorini volcano in the Mediterranean triggered tsunamis that led to the collapse of the Minoan civilization. The eruption's aftermath, including pumice stones, can still be found on Mediterranean shores today. Evidence of the Santorini tsunami was found in Didim and Fethiye in 1997.

An 8.5 magnitude earthquake that occurred west of Crete in 365 generated a tsunami that impacted the entire eastern Mediterranean and caused significant damage in Alexandria. This event is considered a signature earthquake and tsunami for the Mediterranean region. Although the source of the tsunami was on the western side of Crete, it had limited impact on the Anatolian coast. However, evidence of a tsunami that occurred to the east of Crete in 1303 was found in Dalaman. Additionally, a Mediterranean tsunami was recorded in 1036 in close proximity to the Akkuyu region.

Leonardo da Vinci's "Technical Notes," written in 1504, mention the earthquake and tsunami that occurred in 1481. Recently, the lighthouse that existed in Patara at the time of the disaster was found, with a dead body inside. Today, the lighthouse is located 400 meters inland from the shore, with a large area of sand between it and the sea. According to Professor Havva İşkan, the collapse of the lighthouse was likely caused by the tsunami generated by the 1481 earthquake. Further research is needed to fully understand this topic. The destruction of the Patara Lighthouse is a subject that the I'm interested in researching as a retirement project.

KY: It seems that your Technical Notes, like Leonardo da Vinci's, will be a subject of curiosity. And what about the information the Japanese have?

ACY: The oldest information the Japanese have is the Yoga tsunami of 869. The traces of this tsunami were found in the city of Sendai by Tohoku University experts. At that time, the discovery of traces so far inland, 5 kilometers from the shore, was surprising and aroused suspicion. Then the same thing happened in 2011. The Japanese can only go back that far. However, in the Mediterranean, we can get information from civilizations dating back to ancient times.

KY: But are our ancient underwater cities also subject to the fate of tsunami?

ACY: There are such theories for some sunken ports. For example, there are some serious arguments that there are ports that sank because of Santorini. We will investigate that this year. But it is still very unlikely for a tsunami to sink a city. For example, the one in Kekova is called a sunken city, but what happened there is the collapse of the land due to the earthquake. The damage of the tsunami is more to structures and boats. For example, there is the example of Yenikapı in Istanbul. Yenikapı is actually a harbor established after 360. 37 sunken ships were found there. Cemal Pulak is doing research on this subject and states that some of these ships were used within 1000 +- 20 years. Again, there are two big earthquakes dated 989 and 1010 in Marmara. We can say that one of these earthquakes caused some of these ships to sink.

KY: So we have a lot of historical data on tsunamis. So where are the places with the highest tsunami risk in Turkey right now?

ACY: During the 1999 Gölcük earthquake, the fault stopped at the sea, creating a vertical pulse in the Prince Islands in Marmara and raising the risk of a tsunami. Submarine landslides are a significant hazard off Küçükçekmece, Büyükçekmece, Kısıklı, and Yenikapı. However, moving westward, the fault transitions to strike-slip faulting, which can produce tsunamis with up to 50-centimeter amplitudes. Nevertheless, an undersea earthquake-triggered landslide can drastically change the scenario, potentially leading to a devastating tsunami.

It is important to note that the impact of a tsunami is amplified in shallow waters, and the risk associated with a tsunami hitting the shores of low-lying coasts and harbors is much higher. The water depth of the Bosphorus, at 50 meters, means that the risk of a tsunami is relatively low. However, even in the Bosphorus, a tsunami can still cause flooding and severe currents in shallow parts of the strait. The risk of a tsunami is especially high at the mouths of streams, such as the Ayamama stream in Istanbul, where the water can move up to 2 kilometers inland from the stream bed and cause flooding.

In collaboration with the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, we have produced detailed maps that illustrate the level of risk and potential impact of a tsunami on coastal areas in districts along the Marmara coast. These maps are considered to be among the world's best in terms of risk assessment and evacuation planning for tsunamis in Istanbul. The website created by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality provides access to these maps. https://depremzemin.ibb.istanbul/guncelcalismalarimiz/

Regarding the Aegean region, the most recent notable tsunami occurred in 1956 and affected the South Aegean. Additionally, there have been several localized tsunami events in the history of Ayvalık and Çeşme. The tsunamis originating from the Lesbos fault have been known to have an impact in the Aegean. At present, we are working in partnership with the Izmir Metropolitan Municipality to develop tsunami risk and evacuation maps for the Aegean region, akin to the maps we have created for Istanbul.

There has never been a destructive tsunami in the Black Sea region. If there has been one, we do not know about it. The biggest tsunami we know of in this region is the tsunami caused by the 1939 Erzincan earthquake on the Black Sea coast. In that event, water level changes of 50 centimeters were observed in Fatsa and the resulting tsunami was measured by mareographs on the coasts of Sevastopol, Yalta, Kerch, Anapa and Batumi.

There is a wealth of knowledge regarding the Mediterranean region, particularly regarding the subduction zone that stretches from the southern part of the Peloponnese peninsula, through the south of Crete and the east of Rhodes, and enters Anatolia at Dalaman. This fault is capable of generating tsunamis, and one of its branches extends to the west of Cyprus, producing a 5-6 meter pulse. Notably, the 365 earthquake caused a 40-meter displacement west of Crete, altering this part of the island.

The fault responsible for the February 6 earthquake halted at Samandağ and is expected to continue its movement towards the south. Historical records indicate that earthquakes occurred in the region in 551, 996, 1014, 1036, and 1202, making it a high-risk area for tsunamis in the Mediterranean region.

KY: Then let's end this topic with Iskenderun. Did the tsunami play a role in the devastation we faced in the recent earthquake?

ACY: Following the earthquake in Iskenderun, we conducted an on-site investigation and collected information. Although a tsunami occurred, it did not cause any damage or destruction. During our fieldwork, we met with the Coast Guard Command and received their support. The Mediterranean region has a history of tsunamis, as I mentioned earlier regarding the faults leading to Cyprus. After the earthquake, strong currents caused several boats to break their ropes in Karataş, and one boat sank in Yumurtalık. In Samandağ Çevlik fishing harbor, some boats sat on the ground. We reported our findings on sea movements and coastal structure performance to the international community. Despite the widespread devastation across 11 provinces, we did not initially discuss the events at sea, but informed the press two weeks later.

KY: "Tsunami evacuation route" signs were put up at many points in Istanbul. Tsunami information boards were also placed at some points. In other words, we started to see the results of scientific studies concretely in the city.

ACY: Yes, these signs show the safest escape routes in case of a tsunami.

These signs have been installed at many points along the coast in Istanbul. It goes all the way to Bebek in the Bosphorus. Of course, there is not the same level of risk at every point, but for example, there is an important tsunami raid zone in Büyükçekmece. The tsunami risk there is obvious. In this respect, as Boğaziçi University, Kandilli Observatory Earthquake Research Institute and METU, we are working for the compliance of Büyükçekmece district with the Tsunami Ready program in the "Tsunami Ready" project, which continues under the coordination of UNESCO. In this study, our cooperation with Büyükçekmece District Governorship, Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality and Büyükçekmece Municipality continues. A similar program will be implemented for selected regions in Spain, Malta, Morocco and Egypt.

KY: There were some people who found these signs strange. Our people don't like talking about earthquakes and tsunamis, they don't like these issues to be visible, do they?

ACY: Yes, there is such a phenomenon. during our research, we sometimes encounter a common response when visiting tourist facilities and introducing ourselves as METU researchers conducting tsunami research. The response is often along the lines of "There is no tsunami here, why are you studying this?" We have also observed similar reactions in other countries.

KY: In addition to those who found these strange and felt uneasy, there were also those who made concrete criticisms. There are those who argue that the signs are not placed in the right places.

ACY: First of all, it's good to make criticisms, it helps to raise awareness a little bit. After all, the best preparation is awareness. This study is under the supervision of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and one of the aims of UNESCO is to raise awareness.

This work was carried out as follows. At METU, we determined the locations of these signs based on scientific data and submitted them to the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. The municipality, of course, had to get permission from UKOME (Directorate of Transportation Coordination). UKOME examined all the proposed evacuation routes in this study and made changes to some of them. For example, they said that this is an emergency passage road, so we cannot put a tsunami evacuation sign here. Apart from that, in some places, it was seen that the earthquake gathering area was within the tsunami escape area. There is no such thing that there will be a tsunami after every earthquake, but if there is, there will be great trouble in such places. In summary, the project may have shortcomings. These can be corrected with better coordination between the municipality and AFAD.

KY: Speaking of UNESCO, let's talk about the Mediterranean Tsunami Warning System. Is there such a warning system? What is our contribution to this project?

ACY: The Mediterranean Tsunami Warning System was established in 2009 during my presidency of the UNESCO Northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean Tsunami Warning System with the participation of Turkey, Italy, France and Greece. Then Portugal was also included. My esteemed colleague Öcal Necmiioğlu, who is now working in Italy, made great contributions to the process that led there. As a result, there are five tsunami warning systems in the Mediterranean with solid infrastructures. One of them is Kandilli Observatory.

KY: Apparently, the system works because Kandilli issued a tsunami warning for the February 6 earthquake.

ACY: Yes, they applied the decision support matrices correctly and finalized the warning in seven minutes. But they also needed to get confirmation from their expert friends to announce it. As a result, Kandilli issued the tsunami warning 14 minutes after the earthquake. Greece did not issue a warning. Italy issued a warning thinking that if there was a tsunami in this earthquake, it could go all the way there. Then Kandilli also issued a tsunami warning after the earthquake on February 20. Issuing a tsunami warning is a very sensitive task and a great responsibility. Because if you make a wrong warning once, no one will take you seriously for at least 10 years. Kandilli Observatory successfully passed this difficult test. Apart from these, there are of course other warning systems in the Caribbean, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean under the umbrella of UNESCO.

KY: Analyzing the earthquake and measuring its magnitude is something Kandilli has always done, but being able to warn in advance is a very different, very striking development. We have significant shortcomings in earthquake research, but there are also things we do well. How did we get to this point?

ACY: The main reason why we are doing so well on the tsunami is because we have been persistent, careful and internationally cooperative. When we started, there was not much progress, and it was not even considered meaningful to work in this field. But we persisted, and we received support from TUBITAK many times. For example, I personally experienced two of the five biggest tsunamis in the world during our period. The 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean and the 2011 Tōhoku tsunami in Japan. In 2018, after the tsunami in Sulawesi, the Indonesian government allowed the UNESCO team headed by me to investigate. Then the Karakatau volcano erupted in Indonesia and we went to investigate the coasts damaged by the tsunami. In summary, we worked hard and learned a lot. We are now at an important point in the field of tsunami in the world. Let me give an example, the International Atomic Energy Agency prepares specifications and selects five experts from around the world. I am one of them. In short, maybe there have not been very big tsunamis in our country in the modern period, but we have been involved in all the ones that have happened in other places. In fact, once when we were on our way to a meeting in the Caribbean, when our plane was about to land, there was an earthquake on the island of Guadeloupe. There was a tsunami on the small island right next to it. It was pure coincidence, of course, but right after we landed on the island, we became the subject of jokes among our colleagues: "Ahmet Yalçıner, the man who arrives at the tsunami zone the fastest".

KY: Then at least in this field, we can be at ease in Turkey. Together with Japan, we are the country most familiar with the tsunami issue. As a matter of fact, I think the Japanese will confirm this. Because they deemed you worthy of the most prestigious award on tsunami.

ACY: Yes, that's right, the Hamaguchi Prize. It is an award given by the Japanese Government. It is given to scientists and institutions that make original and pioneering studies on tsunamis, storms and marine disasters on an international scale and make significant contributions. Before, it was always the Japanese who received this award. Then they presented it first to an American scientist and then to me in 2019. I'm extremely proud of it.

I would also like to emphasize here that I am proud to have received one of the Marmara Marine Research Awards of the Turkish Marine Research Foundation TÜDAV for 2022.

KY: So let's talk about precautions. A tsunami is a force that destroys everything in its path. How do we protect ourselves from such a force?

ACY: First, let us divide the actions into structural measures and non-structural measures. When we say structural measures, of course, we mainly mean the resistance of structures. We need to build some structures in such a way that they are tsunami-resistant, and here we are basically referring to ports. They need to be built in such a way that they remain operational despite the tsunami. For example, we have done a similar study for Istanbul. The breakwaters of Haydarpaşa Port need to be raised. Another example is the event areas in Yenikapı and Maltepe. These areas need to be made tsunami-proof. There are such priority structures and areas in terms of tsunami.

As for non-structural measures... the most important issue here is to create social awareness about tsunami. We will make our people aware of the tsunami. We will explain when a tsunami happens and how it happens. Especially to our citizens who live on the coastline, work in ports or own boats. We now have an early warning system. We need to spread the signage we did in Istanbul to other regions.

KY: Fortunately, a tsunami is not as sudden as an earthquake. As far as I understand, thanks to the tsunami warning system, we have some time to do something.

ACY: Indeed, unlike earthquakes, tsunamis do not occur suddenly. They have clear warning signs. For instance, if there is an earthquake and the sea starts to recede, this is the most obvious sign of an incoming tsunami. Boats that are near the shore may start to get stuck. If you are at sea, you may have the opportunity to flee into open water in a short amount of time. Running offshore is the best way to protect your boat from a tsunami. If you can reach an area that is at least 50 meters deep, you can survive the tsunami by using engine power. People who are on land should move to a safe area or at least go to upper floors if the structure is sound. Tsunamis can carry away wooden and light structures, but they do not harm solid concrete buildings. Therefore, if we are sufficiently informed and prepared, we have a chance to protect ourselves from the tsunami.

KY: So how much time do we have?

ACY: 7 to 10 minutes in Marmara. But of course, the tsunami warning can only be given in this time. Therefore, it is necessary to take action without waiting for the warning, by looking at the signs. If the waters are receding, for example, you should take precautions immediately. Of course, the weather conditions should also allow this. In other words, there should not be a big storm offshore so that boat owners can escape there. Sometimes this time is even longer. In Sri Lanka, for example, the tsunami came two hours and 15 minutes after the earthquake. But unfortunately, at that time, there was no information that the tsunami could have such an impact in the Indian Ocean.

KY: Can we accurately predict the location and size of a potential tsunami that may be generated by an earthquake with a magnitude over 7 in Istanbul?

ACY: The answer to this question varies depending on the region and district. Unlike earthquakes, tsunami projections differ from one place to another. It is different for Prince Islands and different for Bakırköy. The Istanbul action plan provides a detailed answer to this question, with projections and evacuation plans prepared for each region and district. You can access these documents on the website we have shared the link to. It is recommended for citizens to download and review the file for their respective regions.

KY: Well, last but not least, could you share an evaluation from the marinas' point of view? What should marinas do as tsunami precautions?

ACY: The primary risk for marinas is the potential for being swept away by the strong currents of a tsunami. Therefore, it is important to test existing structures for their ability to withstand tsunamis. Additionally, floating pontoons must be properly designed and anchored to resist the forces of a tsunami. Currently, there is a TUBITAK project being conducted by the Izmir Institute of Technology that focuses on the design of floating systems for tsunami-prone areas. This project will be completed in one year, and the findings will be shared with interested marinas. Another area that requires attention is the review of breakwaters, as narrow entrances can cause water to enter but not exit, resulting in significant damage. It is important to approach these issues with an open mind and a willingness to make necessary improvements.

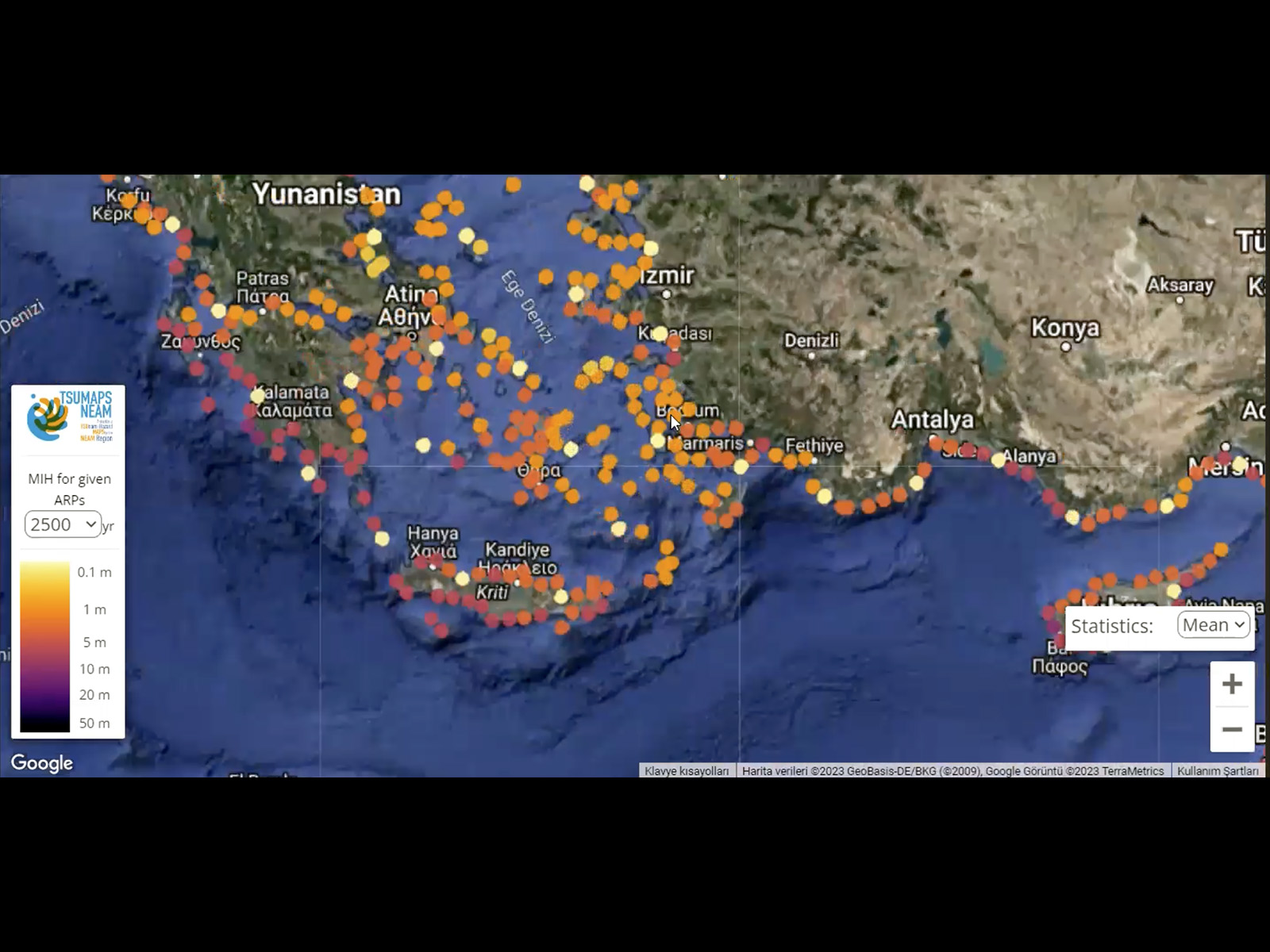

We actually have another project for the coasts of the European Union. It is a site that focuses on the Aegean region in detail. Here is the link to it: https://tsumaps-neam.eu/ Here we have an interactive map, a map based on probabilistic values. You can see the risk areas and risk ratios on this map. We are now preparing a more updated and detailed version of this as a project for the Aegean Region with the support of TÜBİTAK.

Apart from this, I think that the communication activities to be carried out by marinas will be valuable in raising tsunami awareness among both boat owners and the public.

Note from the editor: The marine structures at Setur Marinas in Turkey are designed by coastal engineers. The marinas' emergency action plans include scenarios for earthquakes and tsunamis. The plans have been revised and detailed based on the Istanbul Action Plan. In addition, each marina has an Occupational Safety Specialist and regular plan drills are conducted.

KY: Finally, what would you ask yourself if you were me?

ACY: I guess I would ask why I chose this profession.

KY: Why did you choose this profession?

ACY: Honestly, I've thought about it a lot. One possible explanation is that I have a twin brother and we have very different career paths. He specializes in patents, while I focus on tsunami research. I believe having a twin may have inspired me to pursue a unique direction. Additionally, I strongly believe in the importance of sharing knowledge in the scientific community. When experts from different countries share their research, it leads to progress and advancements. A Japanese expert sends you a presentation, you send him your presentation etc. My brother shares the same view, and we both prioritize collaboration over competition. As a result, we are dedicated to contributing to the shared knowledge pool, and if we have made any breakthroughs in tsunami research, it is because we believe in the power of sharing.

KY: Both the question and the answer were very good. Thank you very much. We would like to see you and talk to you again. But let's hope there is no urgent reason for that.

ACY: It was a pleasure.

Interview: Kayhan Yavuz, Setur Marinas Highlights Editor