İlker Meşe: Ships Have Lives Like People

There is an expression that suits some people very well: Deep sea. İlker Meşe is truly a deep sea. First of all, his job is the sea, his profession is seafaring. Then he writes and publishes seafaring books. He is a collector. He collects objects and artworks related to the sea. He is a civil society member and is involved in many associations for seafaring. Then, on top of all that, he is involved in museums. He is the founder and patron of Turkey's first Maritime Trade Museum. It is not that easy to come across another person who takes on so much responsibility for the sea. But İlker Meşe's primary responsibility is to keep the tradition of seafaring alive. That is the main focus of our conversation too.

Kayhan Yavuz: Let us get to know you a little bit.

İlker Meşe: I was born in Ayancık, Sinop and attended primary and secondary school in Ayancık. I went to Kabataş Boys High School as a boarder. Then I graduated from the Maritime College in Ortaköy. After graduating, I worked as a Watchkeeping Engineer and 2nd Engineer on various vessels owned by D.B. Deniz Nakliyat. Then I worked as a control engineer during the building of 2 vessels owned by Boras Denizcilik and I worked as 2nd Engineer and Chief Engineer on the same vessels. I left the sea in 1989 after about 11 years of sea life and started trading.

KY: You have also been involved in civil society works.

İM: Yes. I worked in non-governmental organizations, I was the President of ITU Faculty of Maritime Studies (YDO) Alumni Foundation for many years. I have been serving as the President of the Ocean Going Chief Engineers Association, which I founded, for two years. I am also teaching at universities as a lecturer. At the same time, I am collecting ship objects. I always act with the people who used them in mind. They are all valuable to me because they have gone through experiences. That is how I got involved in the museum business. The art center and the library also happened spontaneously.

KY: We will talk about them, but where does your passion for the sea come from? Let us ask about that first.

İM: My grandfather. I am the grandson of Captain Meşe from Çatalzeytin. My grandfather is Asım Meşe. My first name is Asım too. My grandfather used to transport salt from Russia on his small boat. When imports started after the foundation of the republic, he started trading. When you mention Azaklı in Çatalzeytin, our family comes to mind. My mother's side is from the Karahan family. The first Mayor of Çatalzeytin is also a Karahan. My father worked for his father and played ball well. This talent got him a job at the Ayancık Forestry Directorate. That is why me and my two siblings were born in Ayancık. My father would never mention our sailor side in our conversations. I only found out much later. It was my destiny to be a sailor. I was born by the sea, I received education by the sea, I worked by the sea, and I still live by the sea today. It is very difficult for me to live without seeing the sea, without looking at the sea.

KY: You make a living from the sea, but then you invest it back into the sea.

İM: Everything we do is all about the sea. We sell marine chemicals at 160 ports around the world. We provide spare parts, calibration. We conduct and interpret oil fuel analyses. We constantly train seafarers in companies and offices. We were the first to do many things in Turkish maritime history. The first chemical importer, the first turbine mechanic, the first fuel oil analysis, the first domestic PMS software, the first marine focused calibration company. We have always considered how we can contribute to our maritime industry and how we can create an alternative for ship owners. I believe we have succeeded in this.

KY: Publishing, collecting, museum business. I have been looking around and your office is full of marine artifacts.

İM: This bell, for example, was a gift from my classmate Muhsin Aytuğ. The top of that coffee table is actually a cabin door. I had legs made for it, it became a coffee table.

KY: Then we should add design to your list of occupations.

İM: What I do is to give beautiful pieces a new function, to make them usable, in other words, to somehow give them a new life. Otherwise they will not stay, they will disappear. For example, you take a lantern, have its wood fixed, and it becomes a lamp. You will end up with something very nice. Even the seats over there are from a vessel. The reception desk at the entrance, for example, was made from an old lifeboat. So is the table in our dining hall, we sit just like on the vessel. Everyone has their own seat, and we have the same meal times.

KY: Does no one object to this? Like, does no one say "Mr. İlker, we are not at sea, we are in the company"?

İM: No, because everyone working here is a sailor. We are all bound by tradition. Also, it is a discipline. Once you have that discipline, you cannot let it go.

KY: How did you get started with collecting? You had purchased a shipbreaking facility in Aliağa, Izmir at one point. Many objects come out of there. Is that how you started?

İM: I started much earlier than that. I always had an interest. I was always thinking about it when I was shipbreaking. Because my view of shipbreaking is different from that of a shipbreaking yard owner. They consider it as a trade, evaluate every single piece, turn them into money. Whereas I, even though I have not worked on a vessel, I can understand and relate to the people who have worked on that vessel. Whatever object they value, I also value. The helm used by the captain is very valuable to me. For that reason, I am the first one to walk around a vessel brought for breaking, looking for parts that can be recovered. By doing so, I took a lot of pieces from each vessel and stored them, recording their names and stories. Of course, it is not an easy thing to do. Removing a part from a vessel without damaging it is a very challenging task.

KY: So the first thing is to get these out, then the rest goes wherever it goes.

İM: Yes, that is the first thing, separating the significant parts. I did that with each vessel.

KY: Alright, but is every vessel important? I mean, are not some of these vessels ordinary vessels?

İM: No, they are not! Every vessel is important. For example, the first vessel we received came from Cyprus. The vessel was completely burned. I tried very hard to find a souvenir on the vessel. I eventually found a tag that was not burnt on the bow, so I took it.

KY: If it were not for you, that tag would have gone for the price of metal.

İM: Of course. Here is my view: That vessel was born. It lived like humans and died when its time was over. It had a life; and you should respect that and keep its memory alive in some way.

KY: I assume that is how you ended up with overflowing warehouses.

İM: When we started the construction of this building, I was not thinking of a museum. However, when we went down two floors to the ground, a considerable space became available. I first started determining their places, little by little. Then I organized the pictures of the vessels and their features and considered displaying them with objects. Thus, a system emerged. Each object having an owner in this system made this museum very different from the others. Therefore, without giving up on it, even if I receive it as a gift, I try to do justice to it by finding the vessel that owned it. Meanwhile, I got a collector's certificate, applied to the state and got everything registered.

KY: So, the museum built itself...

İM: You could say that. When we had the opening, people who saw these started to bring things of their own. It is because people's memories are valuable. But they sometimes do not know what to do with them. We had people taking us to entire libraries.

KY: Why is preserving them so important?

İM: Because maritime trade is a tradition, this profession is passed down from generation to generation. The Maritime College, where we graduated from, has an understanding of brotherhood and fraternity. It is very important for us. We respect our older brothers and protect the younger ones. Studying at a boarding school and sharing a common fate on the same vessels led us to very special friendships. For example, when we go somewhere to eat with my classmates, I warn the waiter to seat us at a table far away. Because when we get together, we immediately go back to the school days, become children again. The seafaring profession involves a lot of discipline because it is a very difficult profession. That is why sailors undergo special training. The discipline that you are introduced to at school must continue once you are on board. We train the young ones for the sea through internships at school. It is essential to prepare the young ones to live in a 4x4 m2 cabin for many months, to deal with the sea conditions and for a steely environment. I emphasize this subject in my lectures and try to prepare the young ones by talking to them. There used to be a Maritime College in Ortaköy that trained civilian officers. It was made a part of the military during the 1980 revolution and suddenly moved to Tuzla. But it had belonged to us since 1927. If you displace the school for no reason, move it to another place, you destroy its history. This caused a huge depression, a major trauma in our community. We all miss that place so much.

Today, we are still fighting to bring our school back to its original location. These are important things. In fact, the books I have written and the maritime museum project are also linked to this. All I strive for is to keep the tradition alive and pass on our knowledge to new generations.

KY: What is the difference between the museum you founded and, for example, the Rahmi Koç Museum?

İM: Mine is a Maritime Trade Museum. There are common objects and pieces of course. But our museum is focused on merchant vessels. Mr. Rahmi also came to visit our museum.

KY: So, you care more about the memory of an object than its value or uniqueness.

İM: Yes, it does not necessarily have to be an extremely valuable, unique piece. What matters is to have a story. For example, we have a small decanter used by Atatürk. We have a sugar spoon from the yacht S/S Ertuğrul, the only reign yacht remaining from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic. We have a sword from the Ottoman Empire. We have lids of dowry chests, with pictures of ships embroidered on them. It was a tradition back then. Women whose fiancé or husband were sailors would embroider this theme on the chests. There is a sentiment here. That is what I care about. You have to look at it this way: You need to start with the Turkish history, move on to the Ottoman Empire and then proceed to the Republic. You must see it as a whole. When you look at it from a historical perspective, everything makes sense.

KY: I will ask this anyway, what is the most valuable piece of the museum?

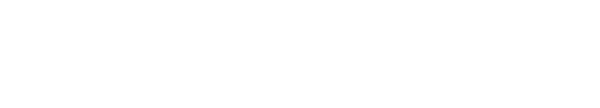

İM: Well, the most valuable pieces for me are the 18 ship newspapers, a wall newspaper that I personally published in 1979 when I was working on the Kocaeli vessel. There is nothing else like it. We write it on a typewriter, so it is a single copy. There was a humor magazine called Çivi, and I used to cut out the pictures from there. Life on the vessel is like this; everything becomes monotonous after a while. You cannot play backgammon all the time. Books or the television will not do it either. You have to produce something; you have to contribute something to life. So I started publishing this newspaper every Wednesday. The sailors (35-36 of us), who did not show much interest at first, started to contribute with their own stories. The entire crew started looking forward to Wednesdays. I took them with me when I left the vessel. I kept them all as if they could reach these days. I still read them and smile with great pleasure.

KY: There is also a different logic behind the exhibition method you use in the museum.

İM: Yes, the visitor should be able to visualize the story of the object. For example, those newspapers I published on the Kocaeli vessel. One day I took those newspapers under my arm and went to the Ülgen vessel in the Persian Gulf. Then I brought them to the house in Kurtuluş. Then I brought them to the workplace. But it did not make much sense to keep and display just the newspapers. When I got my hands on the model of the Kocaeli vessel, it all made sense. When you exhibit the newspapers together with the model of the vessel, the story becomes completely clear, it draws you in. Then you are able to imagine the vessel, too. That is what I did. I started exhibiting the model of the vessel and the newspapers from underneath it together. I also applied this method of exhibition to other objects and documents.

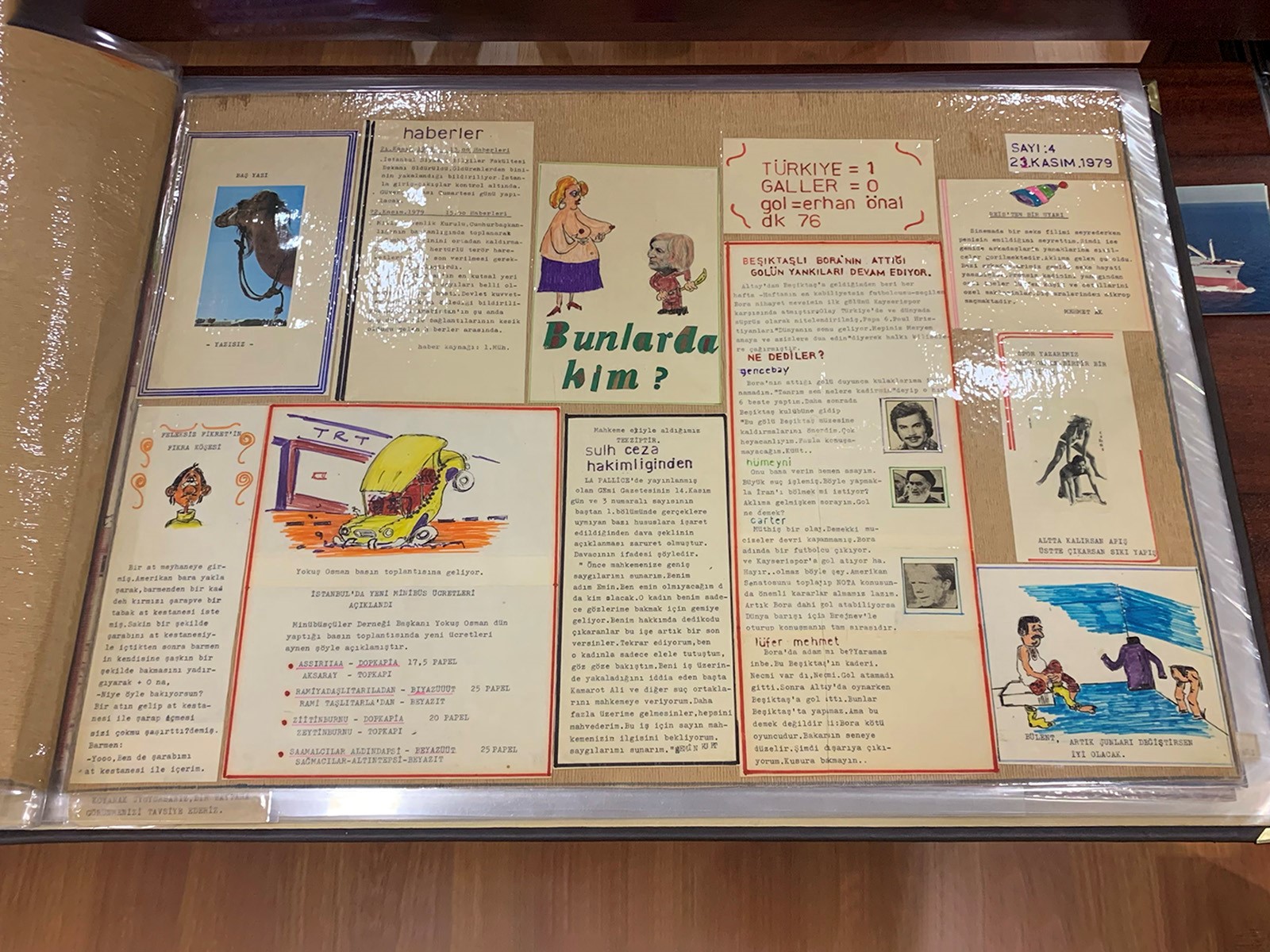

KY: Then it is the perfect time to talk about your identity as a publisher. What sorts of things do you publish?

İM: We have 13 educational books, and we have published 10-12 research books so far. Some of them are published by Denizler Kitabevi, that is, Mr. Turgay Erol. I send important books to him because he is a good editor. For example, Yüksek Denizcilik Okulu Gemileri. That book was published by Denizler Kitabevi. Apart from that, we have community books, such as yearbooks, trade yearbooks. I publish those myself. I also write about maritime trade from the Ottoman era to the present day. For example, S/S Tarsus is our latest book. It is a very important vessel, I wrote and published its story with documents. I would like you to read it. It is as important as the Ankara vessel in American-Turkish maritime history. Because the vessel returned to America. Apart from those, we should also mention the books Osmanlı'da Kurulan İlk Denizcilik Cemiyetleri (First Maritime Communities Established in the Ottoman Empire) or Denizde Örf, Adet ve Nezaket Kuralları (Common Manner, Custom and Courtesy Rules at Sea). What actually matters more to me is this: I am bringing whatever documentation there is on maritime trade into the literature. Thus, I make them available for researchers to work on.

KY: There has been a detachment from tradition in almost every field in recent years. It feels like everything is starting all over again. It is as if the past never existed. What do you think is the reason behind it?

İM: First of all, you cannot prosper without freedom, it is very difficult. However, free people can get somewhere by reading. You need to be able to do it without fear. You must be sure that nothing will happen to you when you write. Remember the revolutions we had. Turkish people have suffered so much. These are necessary for culture to flourish, for tradition to be kept alive. If we do not like reading and research, it is because there is no room for free thought. This leads to detachment from tradition over time.

KY: Do you think we also have an identity problem?

İM: One of the books I am working on is about this subject. The title of the book is Türk Zabitleri İçin Anadolu Tarihi (Anatolian History for Turkish Officers). Why do I want to write that? Because people living in this country must know the history of Anatolia. It is not a question of being Turkish either. The history of Anatolia is the history of Mankind itself. This land is where history was written. We first have to understand this. It is a history dating back 17 thousand years BC. The West learned about civilization from Anatolia. The fact that they look more civilized than us today does not change this fact. So, it is important that new generations know that we have a remarkable history. Thus, they will know their roots and this will lead to a strong sense of belonging and self-confidence. If we do not keep the tradition alive and if we miswrite and interrupt history, there can be no self-confidence in such an environment.

KY: Does this have anything to do with the fact that seafaring is not very advanced in our country?

İM: Those who need the sea become sailors. Like the Norwegians. Like the British. Like the islanders. They need it, otherwise they will starve. There is no other means of transportation for them but the sea. Whereas you experience six seasons at once in your country. Why would you go to the sea? If the abundance of this land is enough for all of us, why go far away? But the new young ship owners, who recognize the potential of maritime trade in the world and are candidates to become global citizens, are growing very fast and well. We are watching them with great attention and pleasure.

KY: What do you think about the state's current approach to seafaring?

İM: The state is you, it is us. Is it not the duty of the state to facilitate the affairs of its citizens, to provide peace of mind and to share wealth? Therefore, if you know what you want, you have to demand it. Nobody will do anything for you if you do not demand it. Well, we lost the passenger ships, but if you put one from Istanbul to Antalya today, would anyone use it? I do not think so. Maybe there will be some people who will board for fun, for nostalgia. We may not prefer a ship when everyone has an automobile and there are airplanes in the air. We should not be too concerned about that. But there is cruise tourism in the world. Italians and Germans are good at it. It is something we can be ambitious about. It is an idea that would work in this geography. Both around Turkey and around the world. You can go to the Caribbean, to America. I honestly think we have been quite late in this regard.

KY: Last but not least, would you like to talk about the environment? Our current issue is environmental pollution and sustainability. How do you think this issue should be approached?

İM: First of all, people involved in the sea and those engaged in maritime trade need to understand this: The sea is your livelihood. You make your living from the sea. If the seas become polluted and uninhabitable, you will lose your livelihood. That is how you should approach and explain this issue. We must relentlessly explain the importance of this to the owners of excursion boats in particular. Then, we should train and test private boat owners and captains. They should know that the slightest pollution will result in the confiscation of their boat or the revocation of their license. Why should these apply to big vessels and not to small ones? This is how maritime culture begins. You can improve it only if you protect it. In every cove I swim at, I pick up two or three full-sized bags of garbage at a time. I really cannot understand people who throw those things. Let me tell you a story about maritime culture... We once went to Norway for training. There, we took a boat to another island for a meal. We left the marina, and as we were speeding along, approaching the island, the captain suddenly stopped in the middle of the sea. At first I did not understand what was going on. Then I realized that it said "4 knots" on the island. It turns out that this speed limit was set because there might be people fishing there or there might be boats at anchor. We went a little further and the captain stopped again. This time we actually saw people fishing. They put indicators on the islands just for speed. Now this is a great example of respect. This is respect for the sea, this is what maritime culture is all about.

KY: Then let us conclude this interview with the hope of becoming a country where the seas are clean and the tradition is passed on uninterruptedly. Thank you very much.

İM: You are welcome.

Interview: Kayhan Yavuz, Setur Marinas Highlights Editor